Valley of Gudbrandsdalen, Norway

The Gudbrandsdalen valley is one of the most populated valleys in Norway, extending roughly 140 km from the town of Lillehammer in the south to the village of Dombås in the north. The area has abundant flood plains along the river, which are extensively used as farmland. Furthermore, due to the scarcity of other available land, many settlements are located along the river.

The valley and side valleys are exposed to various hydro-meteorological hazards, flooding in the main river and tributary rivers, debris flows and debris slides, rock fall, and snow avalanches. Three physical NBS interventions have so far been proposed and approved for the Gudbrandsdalen case site, one of which later has been canceled. The two other proposed and approved interventions, both for flood mitigation, are implemented. A fourth proposal is for a Living Lab stakeholder process, starting ‘from scratch’, with co-defining the problem and the potential solutions. This proposal will not lead to physical implementation.

Photos from the Valley of Gudbrandsdalen, Norway after the flood in May 2013

Jorekstad receded flood barrier

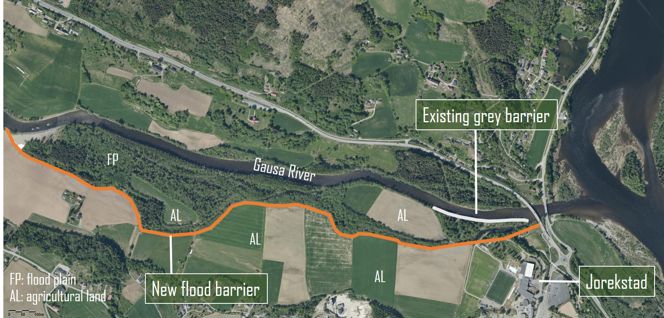

The river Gausa, a tributary river to Gudbrandsdalslågen, experiences regular flooding, with occasional extreme events, such as 1995, 2011 and 2013. The frequency and severity of extreme events is expected to increase over the coming decades. The lower parts of Gausa at Jorekstad, where the river meets Gudbrandsdalslågen, is particularly vulnerable, with agricultural land, housing and infrastructure such as football stadium.

A receded flood barrier, which allows the river to flood the floodplain riparian forest and the nearest farmland during extreme events, will significantly reduce the risk for areas outside of the barrier, and reduce erosion and sediment deposition in the confluence zone with the main river, where this changes the river bottom and leads to increased flood problems.

Aerial photo of the area with the location of the existing flood barrier, which will be demolished, and the new flood barrier. The main river, Gudbrandsdalslågen to the far right (source: NBS handbook, EU).

One of PHUSICOS partner AgenceTer’s ideas of how the barrier could appear.

Co-benefits

In addition to reducing the flood risk of the area, the measure will:

- Preserve the riparian vegetation on the floodplain and enhance biodiversity of this important area

- Carbon storage in the preserved vegetation.

- Reduce runoff of soil, seeds and nutrients, as well as pesticides from flooded farmland and possibly microplastics from nearby football fields with artificial grass

- As it will appear green and nice, it will increase the population’s well-being, support multiple activities such as a fishing platforms, picnic area, and panoramic views, and provide opportunities for hiking, running, etc.

- The building and maintenance of the measure will serve to prove that there are local jobs related to the green shift, and may thus boost the local economy.

Cancelled due to cost overrun

Unfortunately, the detailed design of the barrier revealed that the cost estimate had been far too low, and that the real cost of implementing the measure would be around 100% higher. Great efforts have been undertaken to find a solution to this, including assessing additional funding possibilities, as well as reduced ambitions for the barrier. However, a reduced barrier would not serve the PHUSICOS objectives, and additional funding possibilities have proved far too small.

The consequence is therefore that the receded flood barrier has been cancelled as a PHUSICOS implementation project. However, the Jorekstad project has provided other results in form of experience with governance issues, the WP4 baseline assessment has been done, and the case is still being used as a case for WP6 in their development of VR learning tools for NBS.

Flooding in Trobekken, Øyer municipality

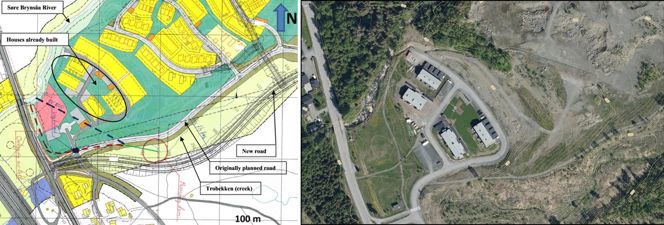

Øyer municipality, just north of Lillehammer, Norway, started a development project to establish 220 family housing units for roughly 500 people in an abandoned gravel pit. However, the project was put on hold due to potential flooding problems and a lack of adequate flood protection. Potential problems in the larger river, Søre Brynsåa River, NW of the development area, will mainly be handled by traditional measures, whereas NBS are installed in the Trobekken Creek. The Creek has a flooding problem during heavy precipitation. It has been closed in the lower part and led through a pipe that ends in S. Brynsåa west of the houses.

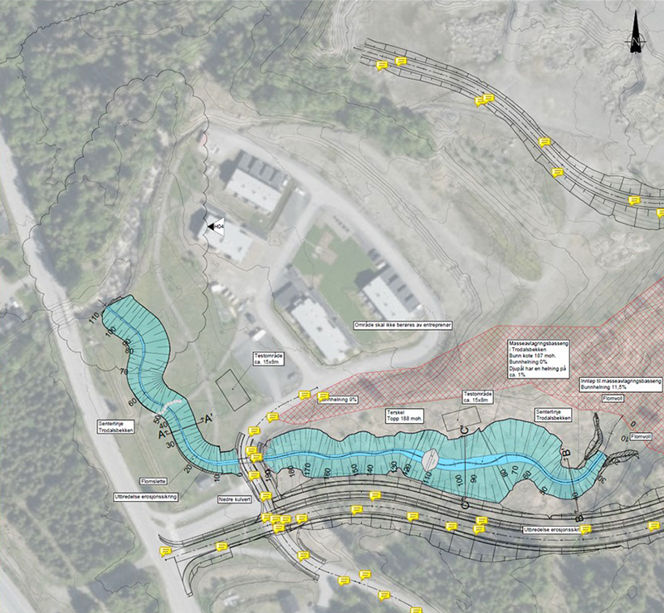

The implemented NBS measures include opening and re-meandering the creek between the built houses and the road. A buffer zone is established around the re-opened creek that will appear as a green recreation area in ‘normal’ periods and as a retention basin during floods. This has been combined with establishing a sedimentation dam (check dam), roughly placed where the red circle is on the map above. Upstream of the check dam, vegetation is used for erosion protection and reduction in energy during floods.

Furthermore, two test fields are established to test out a slightly different plant community than the area at present, mainly to test species that are expected to migrate and become abundant in the region with a warmer climate towards the end of the century. The plants to use along the creek and test fields were suggested in cooperation with PHUSICOS partner AgenceTer and the regional authorities. Care has been taken not to introduce alien species.

The plants to use along the creek and test fields were then suggested in cooperation with PHUSICOS partner AgenceTer and the regional authorities. Only plants that exist in the region have now been used. The two test fields are to monitor the natural re-growth, without any human interference.

Left: Map of the Trodal housing development area before the interventions. The green line and the stippled black lines mark where the creek is piped. Right: Aerial photo of the area as it is today.

Part of the detailed design of the measures in Trodalen. Annotations are in Norwegian. (Design by Norconsult AS)

Left: Drone photo of the completed intervention (without the two test fields) from the fall of 2022 (Photo by Øyer municipality). Right: The lower part of the intervention, also shows one of the two test fields. 2022 (Photo by Øyer municipality).

Skurdalsåa flood retention, Sør-Fron municipality

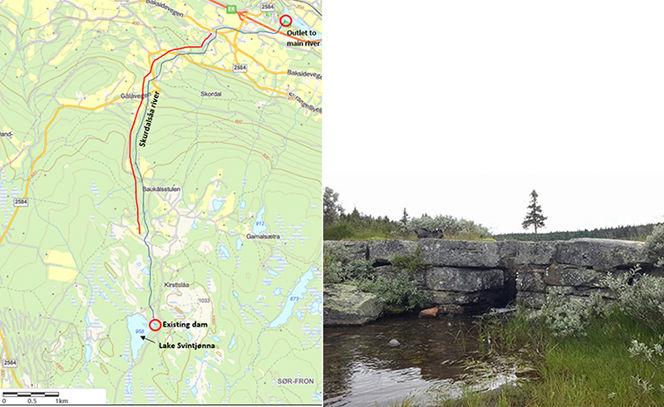

The Skurdalsåa River is one of many steep tributary rivers to the main river Gudbrandsdalslågen. The river has its outlet from an old dam (1870) in Lake Svintjønna. Due to the relatively small catchment, Skurdalsåa responds rapidly to precipitation and snow melt. Roads, houses, a school, a kindergarten, and a sports facility are situated adjacent to the lower part of the river. The infrastructure has experienced repeated flood damage in recent years.

The river course has several bottlenecks, mainly caused by the location of buildings and other infrastructure, but also due to culverts and bridges not dimensioned for the present (or the future) flood situations. Trees and other debris blocking the river at these bottlenecks have caused problems during flooding.

Left: Map of Skurdalsåa. The red line along the river marks the section where selected vegetation clearing is required. The river is ca. 7 km long from the lake to its confluence with the main river. Right: The existing old dam at Lake Svintjønna. The measures will increase the dam height by ca. 0.5 m and establish a new gate and threshold, with automatic monitoring of the lake level.

Implemented measures

The implemented NBS has utilized the old dam (made of local stones, initially built for household water and irrigation purposes) to retain the flooding. The dam is modified by a modest increase of the dam height and lowering the discharge gate, and reinforcing the dam. The spillway is improved and extended. With these implementations, hydrological analyses estimate that the peak flood of a 200-year flood event can be retained by up to two days. There are hundreds of similar old dams in Norway, and the upscaling potential of this relatively simple measure is, therefore, significant.

Additional measures to be implemented over time, but not as part of PHUSICOS, comprise:

- some selective clearing of vegetation that may fall into and block the river downstream

- improve and/or replace under-dimensioned culverts and bridges

Co-benefits include

- increased sense of safety for the inhabitants along the river.

- less potential for damage caused by floods to the valuable river environment, which is maintained by the organization, ‘Friends of Skurdalsåa’

- continued (and improved) the possibility of using the lake for irrigation purposes downstream.

Skjåk Living Lab process for flood mitigation

The municipality of Skjåk in a side valley in the northern part of the Gudbrandsdalen valley, is one of the driest areas in Norway, with a mean annual precipitation of only 300 mm. Most infrastructure, public offices, farms, and family housing are located close to the river. Traditionally this has not caused many problems, but effects of climate change may change the pattern and the intensity of flooding events. In October 2018, a very early heavy snowfall followed by unusually warm weather resulted in a severe snowmelt flood.

This is the background for the Innlandet County Administration’s proposal to run a stakeholder process in the municipality. The PHUSICOS activity in Skjåk does not aim at implementing measures. Still, it is meant to be a complete Living Lab (LL) process, starting from scratch with co-defining the problem(s), and where the aim is to reach an agreement upon a nature-based solution that will be effective and with co-benefits beyond increased resilience. The goal of this process is to introduce viable alternatives to traditional grey solutions and encourage new ways of thinking when faced with the consequences of climate change.

Old waterways in Skjåk as a flood retention measure

During the LL sessions, it was clear that evaluating the use of old waterways for flood prevention was an issue that all stakeholders could agree upon. Because of the very modest annual precipitation in this region, most farmers established waterways leading water for irrigation as well as for households from lakes and ponds in the mountains surrounding the valley down to the fields and the farms. The existing waterways were mostly established in the 18th and 19th centuries, and many are still in use. Although these waterways are made to mitigate drought, their flood retention potential has never been adequately assessed.

It has been agreed to assess the possibilities further through a master’s thesis in hydrology. This has been established at the University of Oslo, Department of geosciences, but will not be concluded until June 2024. The thesis will assess the total capacity of all the waterways in the municipality and discuss what modifications can be done to increase the flood retention capacity.

Similar waterways are established in many of the Gudbrandsdalen Valley municipalities, and the upscaling potential is, therefore, significant.

Flooding in the river Otta through Skjåk in October 2018.

Map of old waterways in a part of Skjåk municipality. The grey tracks are constructed waterways, whereas the blue tracks are natural streams.